- Home

- Linda Newbery

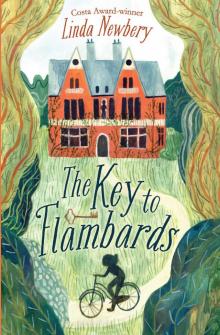

The Key to Flambards

The Key to Flambards Read online

To Kathy Peyton, of course, with love and admiration – and thanks for lending me the key

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

CHAPTER ONE: In Colour

CHAPTER TWO: It

CHAPTER THREE: Just Christina

CHAPTER FOUR: A Line of Russells

CHAPTER FIVE: Snobby + Rude

CHAPTER SIX: Plum

CHAPTER SEVEN: Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines

CHAPTER EIGHT: Something Wrong, Something Bad

CHAPTER NINE: No Plan C

CHAPTER TEN: Full Gallop

CHAPTER ELEVEN: Ghost Soldiers

CHAPTER TWELVE: Marie-Louise

CHAPTER THIRTEEN: Half a Face

CHAPTER FOURTEEN: Bruised

CHAPTER FIFTEEN: Dearest Christina

CHAPTER SIXTEEN: Kicks

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN: Perfectionist

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN: No Accident

CHAPTER NINETEEN: Missing

CHAPTER TWENTY: Love, Even

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE: The Me of Then, the Me of Now

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO: Do You Remember?

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

NOTES

AFTERWORD by K.M. Peyton, author of Flambards

Copyright

CHAPTER ONE

In Colour

It felt strange now to realize that Flambards had been there all the time. It was a real house after all, not just a memory – out in Essex, reachable by train and car in little more than an hour.

‘It’s in colour!’

That was the first thing Grace said when Mum showed her the website. At once she heard how silly that sounded, but Mum laughed, knowing what she meant. Until now they’d seen Flambards only in Granny Izz’s old photos, in black and white. Grace had always thought of it in black and white too, preserved in time like a museum exhibit – the big old house standing proud and alone, walls thick with ivy, windows dark. It had an air of defiance, as if it knew it was marooned in the past, but would stand there until the modern world shoved it out of the way. In the website photo it looked more cheerful; more approachable, with pots of flowers each side of the open front door and two smiling people in the porch, coming out.

Look! it said. I’m still here!

‘It’s been waiting for us,’ Mum said, ‘and we never knew.’

Unlike Grace, Mum had actually been to Flambards – just once, a month ago, after the message that had brought it so surprisingly into their lives. Now, with bags packed for the whole summer holidays, they were on their way there. Soon Grace would see it for herself, the place where Granny Izz – really her Great-Granny – had been born and brought up. Granny Izz had died four years ago when Grace was ten, at what everyone called the Grand Old Age of ninety-eight; if she were around now she’d be the even grander, nearly impossible, age of a hundred and two. She had always been so alert, so keenly interested in everything, even when she was frail and old, that it was still a surprise to find her gone.

Grace felt a bit sad to be going to Flambards without her to show them round. Everything they knew about the place came from her photos and memories. She’d told Grace that she loved Flambards, but had left as soon as she was old enough and never lived there again. ‘London was the place for me. I had to be in London, at the heart of things. Couldn’t bury myself in the country all my life.’ But there had been something wistful in her voice, as if she’d left part of herself behind.

The city sprawl had thinned, giving way to fields and woods. Through the train window Grace saw trees, grazing cattle, a busy road threading through a cut, and now and then a station stop.

‘Ours next.’ Mum put her book and water bottle into her bag, and soon the train slowed again.

It stopped at the smallest station Grace had ever seen, just a brick building on one side of the tracks and a footbridge to the other platform. Following Mum, she clambered down awkwardly, humping her bag behind her. They were the only people who’d got off, and there was no café or waiting room, no one checking tickets or waiting on the platform. A ticket barrier stood open and unattended.

As the train pulled away, taking its passengers and its trailings of city-ness, the silence was broken only by birds singing. Grace was used to busy streets and shops, sunlight mirrored by windscreens and windows, heat bouncing off buildings and pavements. Here the quietness was like a pressure in her ears, almost audible. They walked out into sunshine and a small road where a single car was waiting.

‘Oh good.’ Mum put her phone away. ‘Here’s our taxi.’

She’d booked it ahead; otherwise, Grace thought, looking around, they’d have been marooned in the middle of nowhere.

‘Russell?’ the driver called to them. ‘For Flambards?’

‘That’s us. D’you know the way?’

The driver nodded. ‘I do. Take people up there or back, most weeks.’

While he loaded their luggage into the boot, Mum opened the back door for Grace, waited for her to climb in, then got into the passenger seat. They weren’t used to taxis – in London there were always buses or the Underground, and taxis were expensive – but there was no other way of getting themselves and their baggage to Flambards, a few miles from the station.

‘Some kind of arty holiday place, int it?’ The driver lowered himself heavily into his seat. ‘You off for a holiday, then? Nice weather for it.’

‘Not a holiday exactly, not for me,’ Grace’s mother told him. ‘I’ve got a job there for the summer.’

‘Oh yeah? What, teaching painting, or something like that?’

‘No – in the office. Publicity.’

Settling herself while they chatted, moving her leg to a comfortable position, Grace looked out as the taxi pulled away.

In spite of her doubts about the weeks ahead, she felt a swell of excitement. Just a few more minutes! On the website she’d seen the gallery of photographs, the links to courses on art and history and poetry, but in her mind the two versions persisted, side by side. There was the long-ago Flambards of the photos, back in the days of floor-length skirts and horse-drawn carts and great-great-relatives whose names she muddled up; and there was this one, the real place they were heading for. Mum had said that Granny Izz would barely know the place now. The photo gallery showed sleek bathrooms and people splashing colours on to big abstract paintings, others twisting themselves into yoga poses or laughing in the glow of a campfire.

‘Yes, it used to be my family that owned it, ages ago,’ her mother was telling the taxi driver. ‘The Russells at Flambards go back well over a hundred years, to Victorian times when the house was built. But it was sold before I was born.’

The Russell name, it seemed, meant nothing to the driver. ‘Must have changed hands a good few times over the years, I reckon.’

‘Yes, it has,’ Mum agreed. ‘That’s why I’d never been there till last month. It was privately owned till two years ago – I didn’t even know it was a retreat centre till the new manager got in touch.’

Grace saw hedges and trees; nothing but trees and hedges and fields reaching into hazy distance. The taxi slowed for a tractor carrying a load of hay, and the smell of sweet dry grassiness through the open window made her think of the school field, the running track, the excitement of sports day; limbering up ready to sprint, her legs full of running.

But that was Before, the way so many things were Before. The tractor driver, seated high in his cab, raised a hand in thanks.

‘Be a bit quiet for you, won’t it, out here in the sticks?’ their own driver said, catching Grace’s eye in the mirror. She gave a wincing smile back.

Yes, it would. That was the whole point. Curious as she was to see Flambards, Grace had ba

ulked at Mum’s idea of staying for so long. Wouldn’t just a day visit have been enough?

What was she going to do there? She’d be cut off from Marie-Louise, cut off from everyone – even from the people she didn’t especially want to see. ‘For the whole summer holidays?’ she had protested, when Mum told her. ‘But that’s weeks and weeks!’

Her mother had said that they could both do with a change. As if they hadn’t had more than enough change already! And none of it through choice. What she meant, when Grace pressed, was that they needed a change from being at home – though they couldn’t really call it home any more, with most of their things packed up in boxes.

Grace didn’t like not knowing where home would be. When they’d closed the front door at Rignell Road earlier this morning, it felt like leaving for ever. Where would they go after their stay here? Mum didn’t know, though she kept promising that something would be sorted out.

The taxi had reached a village street. Grace looked out at a pub and an old-fashioned shop – or was it actually a modern shop pretending to look old? – with baskets of fruit and vegetables out on the pavement and loaves of bread in the window. An old man with a whiskery grey terrier on a lead stopped to talk to a woman with a shopping trolley. She thought of texting Marie-Louise: All ancient people round here. Wish you were here! It’d be a lot more fun.

Marie-Louise was in Paris with her parents, having left on the first day of the holidays. When they came back, and Grace and her mother were settled in, she might be able to come and visit. Grace hoped so. Everything would be much less strange if Marie-Louise could be here to share it with her.

‘Not far now,’ said the driver. Beyond the church and graveyard he turned off the road into a narrow drive, bordered by trees. A large painted sign at the junction said, FLAMBARDS – courses, retreats and workshops throughout the year, with a website address and a colour photograph of the house. Now they entered what looked like a private road, fenced on both sides; it led slightly uphill, a wood to the right, a field on the left with sheep grazing. Grace looked out with a sense of travelling farther and farther from everything she knew. If she wanted to get out – to go down to that village shop perhaps, though it didn’t look promising – she’d have to walk there and back. Was there a bus, perhaps, that might take her somewhere else? At least Mum had promised there’d be wifi, so that was something. She could hardly bear to think of six weeks without wifi.

The car turned a bend and the house came into view. There it was: Flambards, leaping into vision with a tug of familiarity, the house of her imagination made real and solid. Huge, it looked, standing square and proud, as if it were saying, Here I am. People come and go, times change, but I’ll always be here.

The taxi pulled round in front of the house and halted with a scrunch of tyres on gravel. Grace tilted her head, looking up. The house reared tall, clad to its eaves in a dark mantle of ivy.

Mum sorted coins while Grace heaved herself out of the back seat and the driver lifted their luggage out of the boot. A white van had followed them up the drive, not slowing as it veered round the parked taxi – barely missing the rear bumper – and went on past, spitting gravel, where the drive curved to the left of the house. Grace glimpsed the curly dark hair of the man at the wheel as he darted a scathing look their way, as if the taxi driver had done something stupid by stopping there.

The taxi man, dumping Grace’s case, raised his eyebrows. ‘Always in a hurry, that one.’

‘You know him?’ Mum asked.

The man jerked his head to one side. ‘Lives in the cottage here.’

Perhaps everyone knew everyone else in a small place like this.

‘Thank you.’ Mum handed over the money. ‘Keep the change.’

He nodded thanks in return and drove off, waving out of his open window. Grace watched him go; he seemed to have become a temporary ally, his friendliness set against the hostility of the van driver. So that man lived here? It wasn’t a good first impression.

The only other people in sight were a man and a woman, both youngish, busy with sketchbooks under the shade of a tree. This tree, an immense cedar with spreading inky branches, was recognizable from Granny Izz’s photographs – unchanged, as if the passing years meant nothing to a tree. Neither of the pair with heads bent over their drawings had taken any notice of the taxi’s arrival and departure.

Stone steps led up to an open front door, flanked by deep bay windows. On each side of the porch stood big tubs bright with scarlet flowers, and a tabby cat lay stretched out on the doormat.

‘What now?’ Grace looked at Mum, whose bright smile showed that she too was anxious.

‘Roger’s probably in the office. He’s expecting us.’

‘Mum, this Roger, and the others here’ – Grace edged closer and spoke quietly, though no one was close enough to hear – ‘they do know about – about me, don’t they?’

‘Oh, Grace.’ Mum put an arm round her. ‘Yes, of course Roger knows. And you’ll like him, I promise. It’ll be fine, you’ll see.’

CHAPTER TWO

It

So much had changed in the last year and a half that Grace felt her old life had been torn into bits and fed through a shredder. First, Mum and Dad’s split, after several months of will-they-won’t-they, with Grace caught in the middle, not wanting to take sides but trying to take both sides at once. That had been bad enough.

And then that day – that May evening that severed Grace’s life into Before and After. That day that should have been marked on the calendar with a big red WARNING sign and flashing lights.

The day of It.

Since then, she’d gone over and over the small things and ordinary decisions that had funnelled her into It, as if It was meant to happen. Without any one of them, the day would have been as unremarkable as any other Thursday, not particularly remembered. If only it had been raining, then she wouldn’t have gone out for a run. If only she’d decided to go the other way to the park, through the alleyways, as she often did. If only her maths homework had been harder, taking her a few minutes longer to work through – a few minutes, a few minutes would have made all the difference between what happened and what so easily needn’t have.

If only the Peugeot driver had taken another route. If only he’d stopped to fill up with petrol or buy chocolate. If only the traffic lights had changed to red a moment sooner. If only he’d been concentrating, not laughing with the woman in the passenger seat, singing along to loud music as he came round the corner too fast, much too fast, beating the red light.

Any of those things could have been different, but they weren’t, and never would be. No matter how many times she replayed, it was always the same – herself running along the pavement, the red Peugeot turning right at the junction, the two of them pulled together as if by a powerful magnet.

The moment when the engine sound became more than that of passing traffic. The car swerving straight at her. The driver’s hands wrenching the wheel, the woman passenger open-mouthed in horror.

I’m dead, Grace thought, trapped by a high wall to her right. She could still recall the instant in which she was able to think that quite calmly.

But next moment she twisted away and leaped, for a wild second thinking she’d jumped clear—

Then the impact, the sickening slam. The car bucked forward as it struck. Her head and shoulder crunched hard against the bonnet. Searing pain carried her away on a dark wave.

That was all she could remember. Letting the merciful darkness wash over her, drown her. Dying must be like that.

Afterwards, everyone said she was lucky not to have been killed. If she hadn’t been pinned against the wall, she could have been flung right through the windscreen.

Lucky.

That depended how you looked at it, and she certainly didn’t feel lucky.

Somehow she was still alive, but they couldn’t save her leg.

She was too drugged and groggy after the emergency operation to take it in pr

operly. It was Mum who told her in words that seemed meaningless, nothing to do with her as she floated in and out of sleep. ‘You’re here, that’s the most important thing,’ Mum kept saying, with a sob in her voice. ‘And we love you, we’ll always be here. We’ll get through this.’

Dad was there too, she was sure he was. Did that mean they were together again?

Much later – hours or days, she couldn’t tell – she was suddenly awake, staring at the ceiling. She registered that she was still in hospital. Did she live here now? Dad was slumped by her bed in a chair, making a small whistling sound as he snored. A drip thing was attached to her arm; she felt a dull pain in her hand, and saw the bandage that held the tube in place and the bag of liquid suspended on a metal stand.

They’d said something about losing her leg, or had she only dreamed that? It was the sort of thing that happened in a nightmare and then you’d wake up, flooded with relief because you were in your own bed and everything was the same as usual. When she glanced down she saw the shape of her left leg – thigh, knee, waggle-able foot – all perfectly normal under the thin blanket; then a cagey shape over the other. So it was there, then. But she kept puzzling, knowing they wouldn’t say that unless it were true. How could her leg be gone?

No. No. They couldn’t chop off part of her. She needed two legs; everyone did. How would she walk? Run? How would she be herself? She tried to wiggle her toes, but only felt heaviness there. Her mind blurred in panic and disbelief.

‘Dad. Dad! Wake up!’

‘Hmmnn?’ He pushed himself up, blinking.

‘My – my leg. What’s happened?’

‘Oh, Gracey.’ He leaned close, cuddling her. ‘Sweetheart.’ He could only force the words out with difficulty. ‘They – they couldn’t save it. It was too badly crushed. They had to amputate below the knee. You’ve still got your knee.’

Even though it didn’t seem real, she found herself sobbing, holding him tight, smelling the clean cotton of his shirt and a faint sweatiness and soap while he rocked her. She knew he was crying too, and trying not to. At least he didn’t tell her she was lucky.

The Key to Flambards

The Key to Flambards Catcall

Catcall Sisterland

Sisterland Lucy and the Green Man

Lucy and the Green Man Set In Stone

Set In Stone Lob

Lob Andie's Moon

Andie's Moon The Shell House

The Shell House Girls on the Up

Girls on the Up The Sandfather

The Sandfather Missing Rose

Missing Rose Polly's March

Polly's March Quarter Past Two on a Wednesday Afternoon

Quarter Past Two on a Wednesday Afternoon Flightsend

Flightsend At the Firefly Gate

At the Firefly Gate